The network analysis of the Collective Natuurrijk Limburg reveals the various actors involved and their (formal and informal) relations. The well-developed practice of cooperationSee collaboration. More between the actors contribute greatly to the success of the scheme, even though some challenges could be detected. The social capital (trust, knowledge exchange, social cohesion etc.) within the network is crucial for the effectiveness of the measures and the motivation of farmers to join a collective.

This study focuses on one of the forty existing collectives, located in the South-east of the Netherlands. The collective Natuurrijk Limburg covers the whole area of the Province of Limburg and has about 1300 members, making it the largest of all Dutch collectives.

This research uses Social Network AnalysisSocial network analysis (SNA) is a methodological approach that has been found very useful in dissecting and better understanding complex governance arrangements. In this context, it has been applied in numerous studies to underst... More (SNA) which is an umbrella term for a body of research methods that try to analyse underlying structures of social networks. Important actors, as well as their formal and informal connections, motivations and influences are inquired. Relevant interviewees were identified through referral sampling and eight interviews were conducted in total. Thereby we ensured to cover different views from farmers, representatives of the collective as well as governmental organizations. Five respondents are on the provincial level in Limburg, while three are on the national level of the ANLb (ANLb – Agricultural Nature and Landscape Management).

The research was guided by the following two research questions:

- Who are the central actors and how do they interact?

- In which way does the presence of social capital influence the functionality of the network?

GovernanceThe process of formulating decisions and guiding the behaviour of humans, groups and organisations in formally, often hierarchically organised decision-making systems or in networks that cross decision-making levels and sector bou... More Tasks are Decentralized and Partly Outsourced from Governmental Responsibility

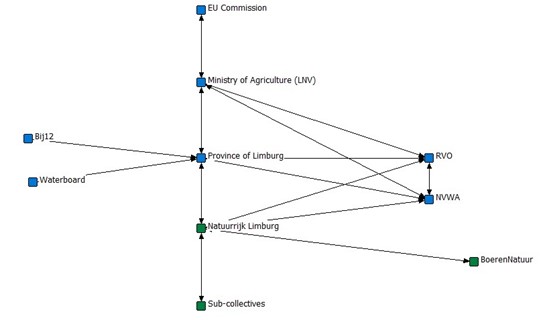

The formal network representation (Figure 1) shows the decentralized approach of the agri-environmental program. Basically, the framework conditions are set on EU and national level but the province is the responsible authority that carries out the program in collaborationPeople working jointly towards a common goal, involving regular interaction among the collaborating individuals. May also apply to organisations. Belongs to the range of collective approaches. Synonym: Cooperation More with the collective through the so-called “front-door-back-door”- approach of contracting. However, governanceThe process of formulating decisions and guiding the behaviour of humans, groups and organisations in formally, often hierarchically organised decision-making systems or in networks that cross decision-making levels and sector bou... More tasks are shared among different actors in a more complex way leading to cross-level feedback loops.

Fig. 1: Network representation of formal relations

The province is involved in decisions on the national framework of the program. There is an execution unit for nature related issues from the 12 provinces (Bij12) that supports them with information exchange and advice. In this way, regional concerns are considered in fundamental decisions. In addition, regional interests from the collectives are represented by their umbrella organization BoerenNatuur through participation in the national steering meetings. They are the voice for the collectives. BoerenNatuur also disseminates information from government or nature conservation organizations to the collectives. As an important service for the collectives, BoerenNatuur runs an IT-system that allows the collectives comfortably to indicate which measures are implemented at plot level. The very well-designed IT-System increases also increases flexibility by enabling a “last minute management”. The role of BoerenNatuur as a linking actor is not to underestimate. Yet, interviewees on local level did not name them as important because they may have no direct contact with them.

Regarding the checking of the agreed measures, there is a parallel structure. Central government authorities (RVO and NVWA) audit the fulfilment of the contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More at an administrative level and on a random basis also at the field level (on-the-spot checks). The collective itself undertakes checks at field level which often help to identify difficulties in fulfilling the contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More early on when adjustments are still possible. In consequence, the province decides on sanctions in the form of reduced payment to the collective in case the controlling agencies detected errors. The collective however decides how they deal with non-compliance of individual farmers according to their statutes (e.g. “red card” with the requirement to repeat the measure, reduced payment etc.).

The Importance of Social Capital for the GovernanceThe process of formulating decisions and guiding the behaviour of humans, groups and organisations in formally, often hierarchically organised decision-making systems or in networks that cross decision-making levels and sector bou... More Network

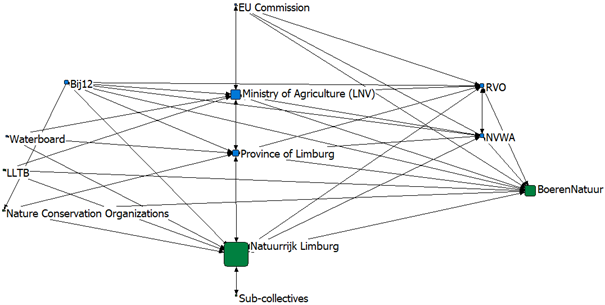

Informal relations between the actors make the network much denser (see Figure 2). These relations are important for knowledge and information exchange in parallel to the formal communication channels. They also connect actors who are not connected formally, e.g., the collective and nature conservation organizations, or the regional water board, who have ecological expertise and data that are necessary to plan targeted measures. Another example is the integration of the farmers’ association in Limburg who contribute agronomic expertise and have certain influence on the members. Informal relations can be seen as a complement to the formal ones.

The social cohesion within the collective, among members and between members and the organization is important to motivate members to engage in the program. Therefore, the collective organizes meetings and exchange of small groups on the field. Since Natuurrijk Limburg is a large collective, there cannot be personal relationships between all members. The nested structure of four local sub-collectives who can bring members in their territory together helps to maintain connectedness to the collective at the regional level.

Hence, it is important that the staff at the regional level also tries to be in direct contact with members. In that sense, the fieldworkers play an essential role. They are hired by the regional collective and maintain the direct communication with members through providing advice on site. They do the on-site checking of the agreed measures for the collective. They do this in dialogue with the members of the collective, which contributes to a feeling of trust in the organization and the program in general.

Social capital also facilitates cooperationSee collaboration. More between heterogeneous actors that differ in organizational backgrounds, interests, or formal power hierarchies. Joint evaluation of collective and province on a regular basis on how the program works is important so that solutions to potential bottlenecks can be discussed. Besides planned budget cuts several interviewees stated a lack of support from the province, meaning rather the decision-makers than the people from the administration, in terms of developing a shared vision and promoting the collectives’ work in the region. However, regarding the formal contracting, the collective and the province work together efficiently. The fact that individual farmers no longer need to negotiate with the government in case of dissatisfaction on how measures were carried out is highly appreciated by all actors.

This text is an excerpt of a research note written by Berner, R. & Barghusen, R. (2022)

Check out this blogpost featuring the developments in the two Dutch Contracts2.0-Case studies.

Photo by Harm Kossen (Natuurrijk Limburg)