Willingness to collaborate in agriculture? A behavioural experiment shows positive results

Many environmental objectives in agriculture can be better achieved at larger spatial scales through cooperationSee collaboration. More among farmers. In the Netherlands agri- environmental measures are implemented exclusively within farmer collectives (“Dutch modell”), which develop regional management plans together with the authorities. In a behavioural experiment, we investigated German farmers’ willingness to collaborate with the aim to introduce such an approach to Germany.

The participants’ willingness to collaborate was high and exceeded the expectations of experts. These results provide first positive indications regarding the potential of collaborative agri-environmental schemes (AES)usually comprise several agri-environment-climate measures (AECM). Synonym: Agri-environment-climate schemes See also: Agri-environment-climate measures (AECM), Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) More in Germany.

(German version /deutsche Version)

Motivation and goals

There is great interest in the “Dutch approach” of collectively implementing agri-environmental schemes (AES)usually comprise several agri-environment-climate measures (AECM). Synonym: Agri-environment-climate schemes See also: Agri-environment-climate measures (AECM), Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) More , since many measures are more effective, when coordinated on a landscape scale, e.g. rewetting of peatlands, protection of habitats or erosion control. The 2019 report of the Scientific Advisory Council at the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture therefore also recommends: “(1) Examine the extent to which elements of the Dutch system of collective nature conservation arrangements could also be applicable in Germany; (2) improve the institutional prerequisites for the implementation of collective models of environmental and climate action; (3) in pilot projects in the current finance period, support the grouping of relevant local actors into ‘biodiversity-generating communities”.

However, little is known, about the willingness of farmers to collectively pursue environmental goals. We have investigated this basic willingness in a so-called public goodsGoods where access to the good cannot be restricted and where use by one individual does not reduce availability to others. See also: Environmental Public Goods More game.

The public goodsGoods where access to the good cannot be restricted and where use by one individual does not reduce availability to others. See also: Environmental Public Goods More game

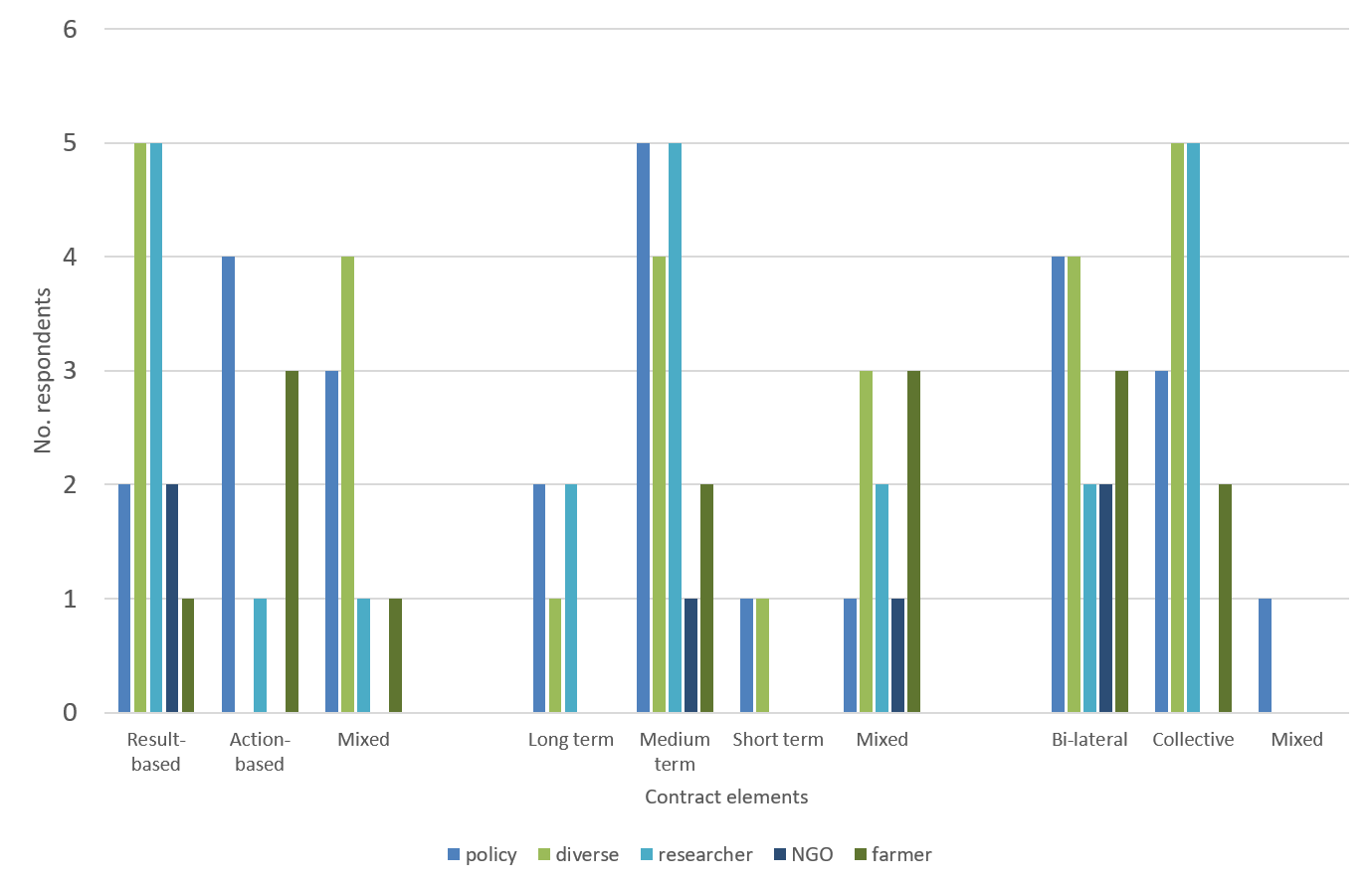

The public goodsGoods where access to the good cannot be restricted and where use by one individual does not reduce availability to others. See also: Environmental Public Goods More game is a concept from game theory (theoretical framework within the field of economics). Players have an initial monetary endowment that must be divided between a private account and a group account. The money in the group account is multiplied by a number that is lower than the number of participants but greater than one. Thus, although it is in the interest of the group, players have no individual incentive to contribute to the group account, although this is in the interest of the group. The game can be used to abstractly study free-rider behaviour and cooperationSee collaboration. More. Thousands of laboratory experiments show that many people are willing to cooperate with strangers. A typical result is that participants contribute about half of their initial endowment to the group. The figure (above) shows an example with four players and an initial endowment of 10 euros.

The experiment and the survey of experts

Public goods gamesare a widely applied economic experiments. In a public goods game, a group of people is endowed with resources which they can either place in a private or a joint account (public good). In a standard linear voluntary contributions... More have already been carried out in many different versions in the laboratory. In our study, we discussed a selection of possible treatments against the background of collaborative agri-environmental schemes at a workshop during the Green Week 2020 in Berlin. In addition to a baseline version, four treatment versions of the game were selected from 17 alternatives for a study with German farmers:

(1) Baseline: four participants must allocate 50 euros between a group account and a private account. The amount on the group account is doubled and divided equally among all players.

(2) Heterogeneous initial endowment: participants have either a high or a low initial endowment;

(3) Leading by example: three participants can first see the decision of the first player and only then make their decision;

(4) Social norm: participants receive the information that many other participants have contributed high amounts to the group account;

(5) Social optimum: participants receive the information that it is in the interest of the group that everyone contributes as much as possible to the group account.

More than 350 farmers participated in our online experiment. Participants were randomly presented with one of the five options. Every tenth participant received a real payment depending on his/her own behaviour and the behaviour of the other participants.

Parallel to the study with the farmers, we asked more than 200 experts from science and practice to predict the behaviour of the farmers in our experiment. Three participants were randomly selected and received a payment depending on the accuracy of their estimate.

Results

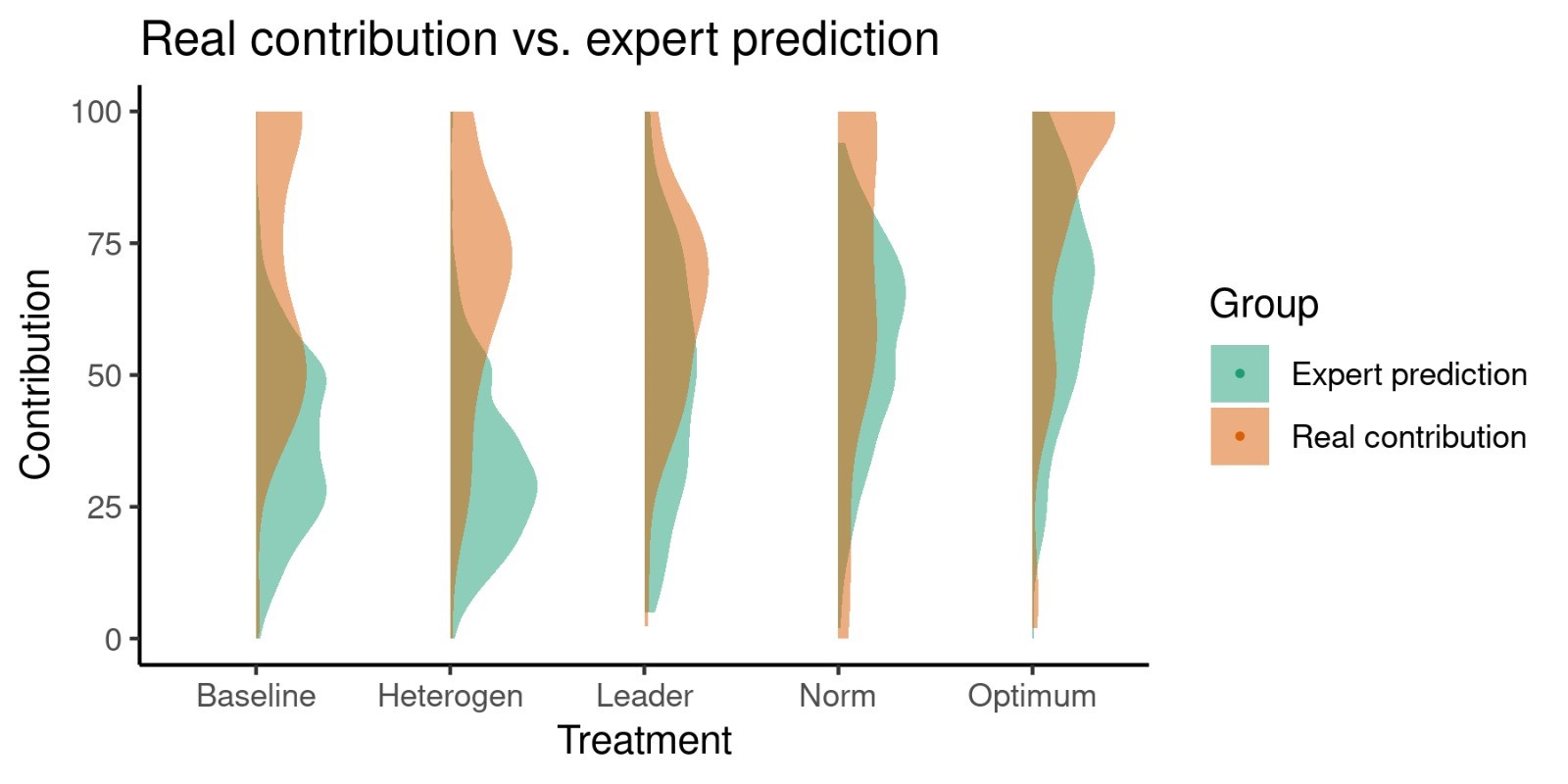

For each of the five treatments the figure shows in orange the distribution of the percentage that participants contributed to the group account. In all treatments the average is higher than 50% and, thus, higher than in typical laboratory experiments. The contributions do not differ between the treatments, with the only exception of the social optimum, where contributions are significantly higher and reach 80% of the initial endowment.

The distribution of experts’ predictions is shown in green. Experts underestimate the contributions of farmers by an average of more than twenty percentage points.

First conclusions and outlook

The most important conclusion is that participating farmers show a high basic willingness to cooperate under experimental conditions. It has also been shown that experts assess the cooperationSee collaboration. More behaviour of the participants too pessimistically. In the Contracts2.0 project, we will now discuss these results with practice partners and gather insights into the potential of collaborative agri-environmental schemes and the so-called “Dutch model” in further studies. Among others, similar studies are planned in the Netherlands, Hungary and Poland. An English-language report describing this process is available for download:

Rommel, J., van Bussel, L., le Clech, S., Czajkowski, M., Höhler, J., Matzdorf, B., … & Zagórska, K. (2021). Environmental CooperationSee collaboration. More at Landscape Scales: First Insights from Co-Designing Public Goods Gamesare a widely applied economic experiments. In a public goods game, a group of people is endowed with resources which they can either place in a private or a joint account (public good). In a standard linear voluntary contributions... More with Farmers in Four EU Member States. https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/23419/

Publication update: The full study has now been published (August 2022). https://academic.oup.com/qopen/advance-article/doi/10.1093/qopen/qoac023/6677430?login=false

Title Photo by Warren Wong on Unsplash