Knowing farmers’ motives helps to strategically address participation

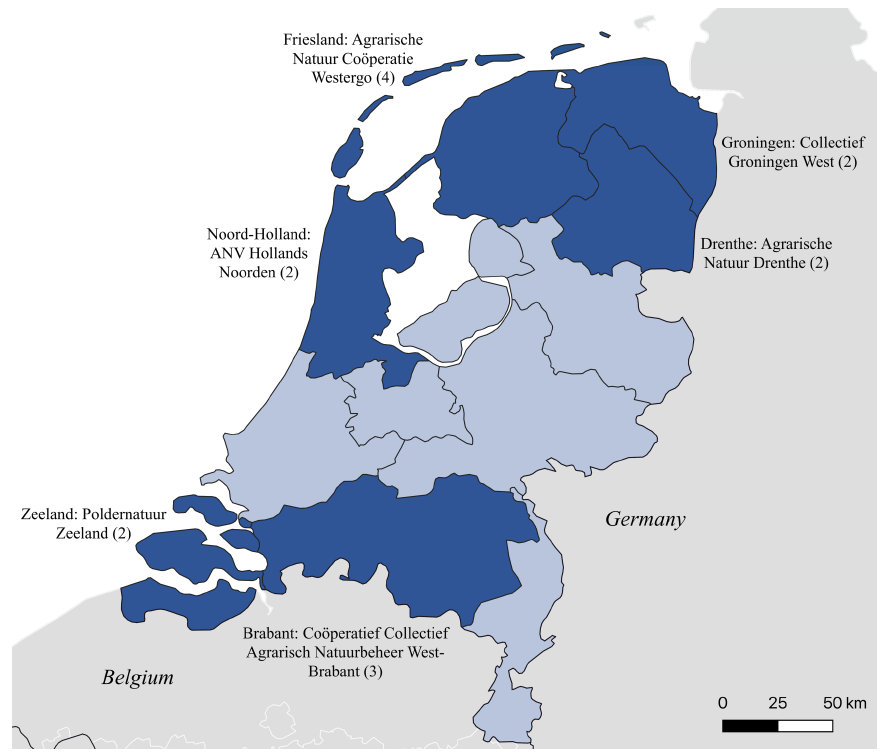

What are the most important motives for farmers to participate in collective schemes? Researchers from Leibniz Centre of Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF) collaborated with BoerenNatuur to ask people involved in the Dutch agricultural collectives about their perception.

Being in close contact with the farmers, the agricultural collectives play a key role in motivating farmers to participate in decision-making, knowledge and capacity building and carrying out measures. For successful landscape management with improvements for nature, it can be important to motivate the “right” farmers. For example, those who manage lands in focus areas or those who always lived in the region and have the best local knowledge. The expectations of the collectives on farmers’ motivations make a difference in the way they approach and recruit farmers.

Identifying Key Motives

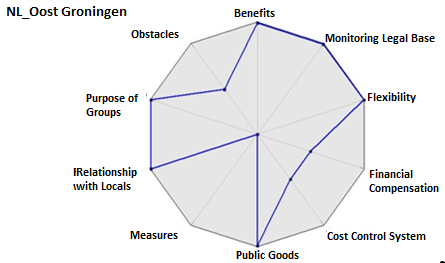

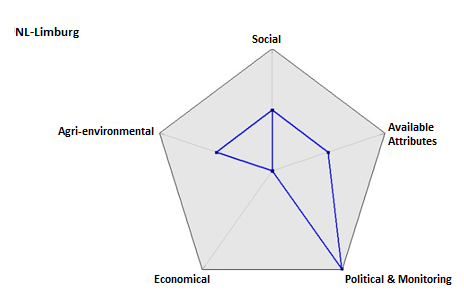

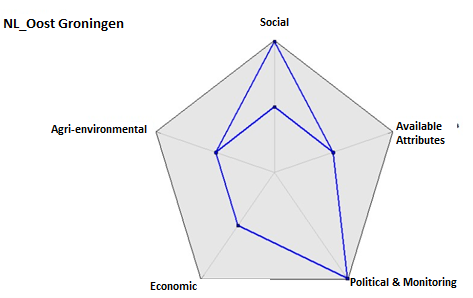

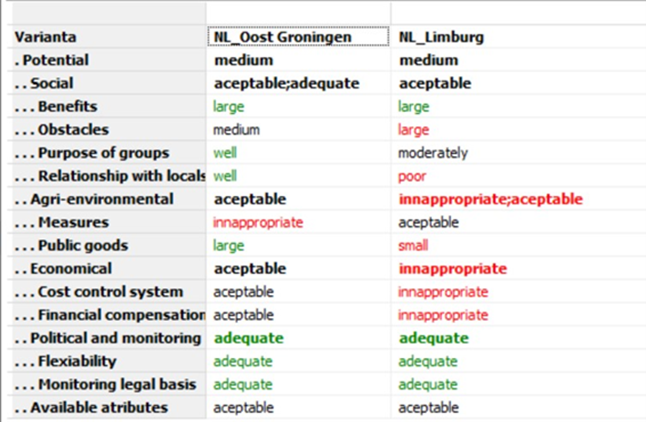

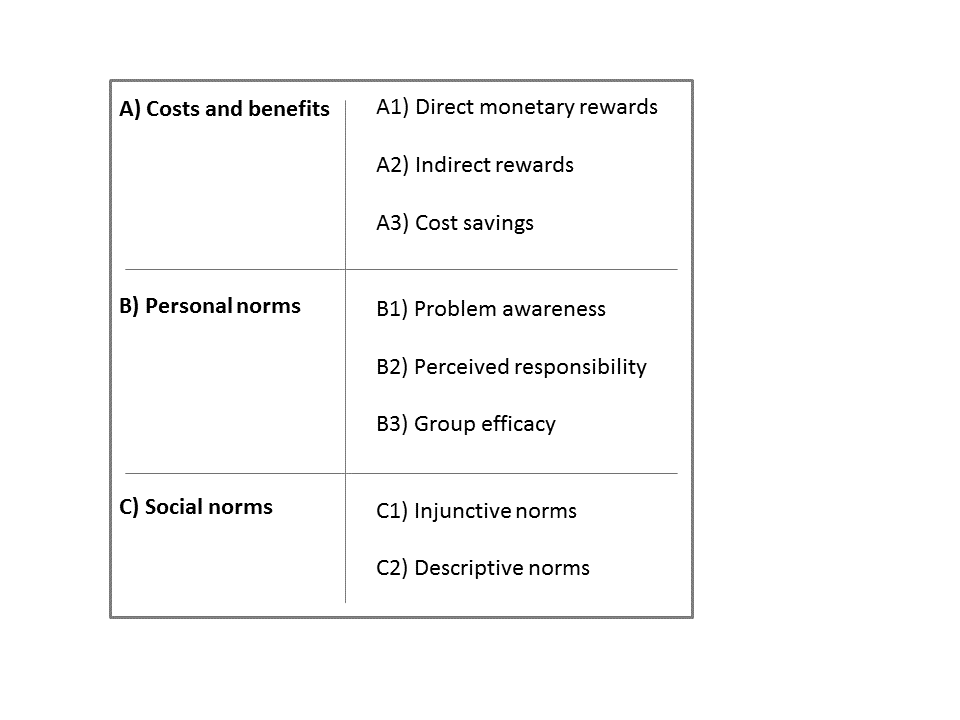

In order to support the targeted approach in “pushing the right buttons”, researchers from ZALF (Germany) and BoerenNatuur (Netherlands) collaborated on a study to identify the most prominent aspects motivating farmers to enroll in Agri-environmental programs. While the relevant categories for different motivations (Figure 1) were identified via a literature review, their applicability was pre-tested in a workshop. After the relevance of the individual aspects of motivation was confirmed, the framework was the basis of a survey asking the people involved in the collectives to rank the different aspects according to their importance.

Figure 1: Categories of farmer motivations to participate in collective agri-environmental schemes (Barghusen et al. 2021).

Intrinsic Motivation is Equally Important

The results revealed that farmers can be motivated by thinking of costs and benefits from participation: that can be the payments directly, or indirect benefits like support from the dairy sector. But an economic motive is in most cases not the only explanation. Intrinsic motivationsrefers to behavior that is driven by internal rewards (i.e. the motivation to engage in a behavior arises from within the individual because it is naturally satisfying to him). See also: Extrinsic motivations More, such as personal awareness of nature and problems like biodiversity decline as well as a feeling of personal responsibility can be quite powerful. Respondents of the survey were convinced that these motivations play an equally important role.

Three other categories of motivation were analyzed: There is first the belief in the groups’ effort, that farmers working together can have a greater impact. There is also the aspect of having had long-term experience with working together of some of the agricultural collectives. They often share norms like commitment to nature. And then there is also the aspect of perceived peer pressure, when a farmer is motivated due to the wish to be seen as a good farmer by colleagues.

Understanding the Motives Better Helps to Increase Enrollment

We assume that these socially influenced motivations are essential in the collective system, although, in this survey, it remained rather unclear to what extent. Moreover, it may depend on the degree of interaction between actors. Practice, however, shows that many agricultural collectives already strategically engage in facilitating personal exchange and cohesion in the collectives, but also in connecting with local citizens or companies.

The question is whether all collectives are well aware and strategic about diverse motivation of farmers, especially the social dimension? Findings from the survey suggest, that collectives differ in awareness of their role in developing social capital. They could further engage in exchange among each other on how to address economic, personal, and at the same time also social ways in which farmers relate to biodiversity preservation.

For more information as well as details regarding the underlying data please check out the full article.

Written by Rena Barghusen (ZALF, DE)

Photo by Annemieke Dunnink (BoerenNatuur, NL)