Now You See Me – Can Consumer-Labels help promote the Provision of Ecosystem Services?

Many studies show that consumers may be willing to pay a premium for food products with additional value such as regional production, certain social standards, or biodiversity related aspects. But what is needed to convince food processors, retailers, and other value chain actors to engage in the process of developing products reflecting this societal demand? After all, establishing the necessary structures, relationships and institutions is, at least initially, a rather costly process. In Contracts2.0 we conducted a study asking food industry experts, how a value chain approach could help to ensure the long-term provision of ecosystem services.

Labels can help consumers make informed choices

There is theoretical evidence that consumers would pay a higher price for higher production standards. Especially, when farmers, being on the forefront, are sufficiently compensated for making the additional effort to bring about the desired ecological impact.

But – this must be clearly communicated to consumers! Labels can help the consumer to make informed choices by marking the added value of a product. While this can be very helpful when making a purchase, it is easier said than done. Every time we enter a store, we are confronted with endless options and ample choice. Yet every consumer reacts differently to the various marketing instruments used to prompt purchases. Therefore, some experts say, that relying on just one instrument for promoting the added value, such as a label, does not suffice and it should rather be a mix of different instruments (Label, QR-code, Point-of-sale instruments), so consumers can pick the one most suitable for themselves.

In line with that, the current EU Farm to Fork strategy intends to integrate a sustainable labelling framework to empower consumers to make sustainable food choices. However, the European Commission has not yet been explicit about how to implement this. Since the idea of “sustainable” can be interpreted in many ways, in Contracts2.0 we wanted to test how we can use product labelling to increase the provision of Ecosystem Services in particular.

What do experts think about a new labelling framework for Ecosystem Services?

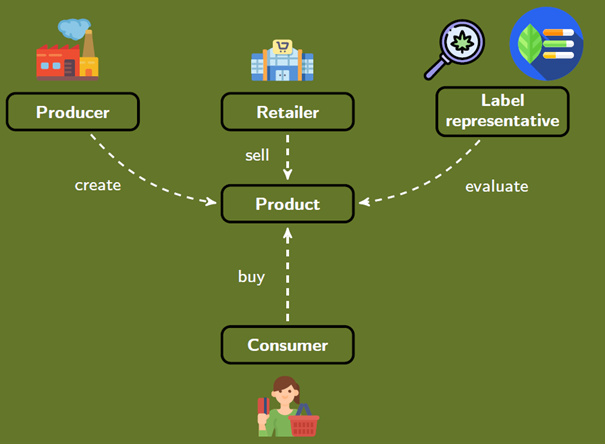

To successfully implement a new label, all stakeholders along the food value chain should be involved in its design process. We interviewed producers, label organisations and retailers in Germany, Poland, Spain, and Sweden to find out where the 45 participants see potential for the introduction of a new product label for Ecosystem Services. The experts were chosen due to their particular expertise in consumer behaviour and valuable insights in gaps in the current labelling landscape.

Figure 1: Food value chain actors considered in the study (Icons from freepik, flaticon.com).

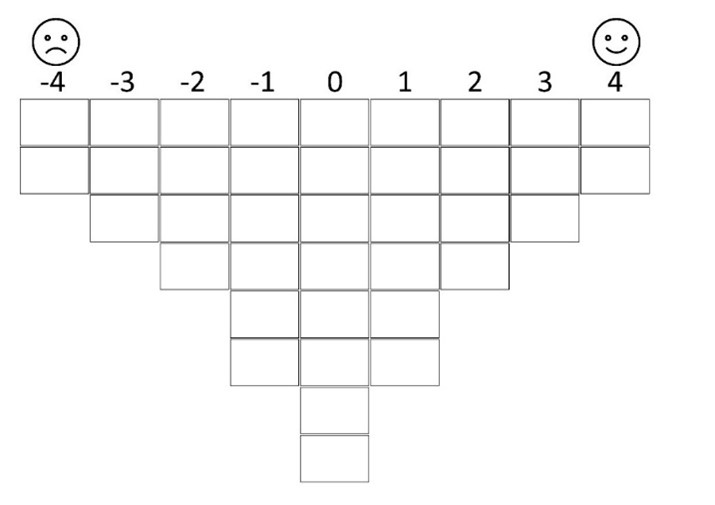

To learn about the individual attitudes towards a new label, we asked participants to sort prepared opinion statements according to their personal agreement with it and justify their placement. This way we were able to compare and analyse the experts’ opinions and categorise them into common viewpoints. More than half of the experts were in favour of such a potential Ecosystem Services labelling framework and even proposed concrete recommendations for its design. A smaller part of the expert group was rather critical of introducing new Ecosystem Service product labels, either because of the multitude of already existing labels or the technological requirements to successfully track provided Ecosystem Services along the value chain.

Figure 2: Example of a grid in which statements were sorted into.

Where do we go from here?

We used the identified similarities to develop and propose three label prototypes that differ in terms of presentation and verification of services, rewarding farmers, and relating products to verified producer services.

1) A producer-driven Ecosystem Services label: this label is independent of any existing labels and only focuses on the provision of Ecosystem Services in the value chain rather than any other product characteristic. Farmers are directly remunerated according to their contribution and independent third-party organisations verify the compliance. The mechanism behind this label is similar to EU organic: farmers receive subsidies for their environmental effort and are able to realise market advantages because of their distinguished products.

2) A consumer-oriented information label: Here, we argue that increased visibility through the label increases the product’s demand enough to lead to higher product prices. The farmer in this model is not directly remunerated by the government for additional effort (such as with pillar 2 payments with respect to organic farming) but rather compensated by higher market prices, since consumers are likely willing to pay higher prices for these high-quality products. In contrast to the first label type, which is backed by third party institutions, this label is being verified by national governments and existing policy mechanisms. In that line, the monitoring can be done by already existing organisations, such as it is currently done in the case of agri-environmental climate measures.

3) A reformed EU organic label: similar to the mechanism of the second prototype this one aims at using market advantages ideally resulting from increased demand though existing but extended environmental labels. Specific Ecosystem Services are clearly linked to the product rather than a general classification as “eco-friendly product”. Here also, existing institutions could be used for certification and thus help to streamline the process. So, this can be seen as an extension or redefinition of the already existing EU organic label.

Informed by various experts, our findings can contribute to the current discussion on the design of the sustainable labelling framework under the Farm to Fork strategy.

In the next steps we want to test whether consumers are actually, and not just in theory, willing to pay for products that are certified to be particularly biodiversity-friendly.

The detailed results have been summarised in a study that is currently under peer review. When publicly available we will link the study here.

Ⓒ Christoph Schulze, ZALF

Ⓒ Title picture: Lyza Danger Gardner