Exploring feasibility of novel approaches – A Delphi study

The team from ESSRG, overseeing the policy work package in Contracts2.0, conducted a Delphi-survey to highlight limitations of the current agri-environmental schemes as well as to gauge the perception of innovative approaches for the delivery of public goodsGoods where access to the good cannot be restricted and where use by one individual does not reduce availability to others. See also: Environmental Public Goods More amongst policy makers, farmers/advisors, researchers and NGO’s across Europe.

The Delphi methodThe Delphi method is a systematic and interactive forecasting method relying on a panel of experts. In policy relevant situations Delphi is usually used to develop consensual ideas on potential policy pathways by paying attention ... More is based on structured expert surveys and draws on experiences and knowledge of the participants in form of empirical, predictive and normative aspects. Its core concept is to facilitate discussions and develop consensual ideas among participants via several correlated rounds allowing experts to reconsider their opinion in each round.

It is planned to run altogether three rounds of the Delphi survey, to assess the knowledge base and to stimulate a discussion regarding the adoption of innovative contractual solutions for a farmer- and eco -friendly agriculture. The first round of the survey, conducted in March/April 2021, was completed by 41 stakeholders form 17 European countries. The aim was to first depict the limitations of current agri-environmental schemes, followed by an assessment of the knowledge base and experiences regarding the four novel approaches being at the heart of contracts2.0: results-based paymentsare an approach where farmers and land managers are paid for delivering environmental outcomes, for example for enhancing the presence of important grassland species. In these schemes, farmers determine the management required to ... More, collective action as well as value chain and land tenure approachessuch as land use obligations in combination with reduced rent, or land use rights combined with specific land stewardship obligations, are an approach specifically for long-term nature conservation objectives. Furthermore, land te... More. In the following some of the results are summarized:

Limitations of the current schemes are evident

Regarding the limitations the results suggest, that financial (e.g. transaction cost, compensationIn the sense of the polluter pays principle: Compensation of the loss of performance and functionality of the ecosystem through appropriate measures. In the sense of incentive creation: A remuneration (typically based on the conce... More vs. rewardRemuneration for current ecological achievements (e.g. biodiversity, climate or water protection) without a necessary additionality. See also: Compensation More) and institutional (e.g. bureaucracy, lack of flexibility) factors are the most relevant. But knowledge-related aspects (e.g. lack of robust scientific evidence, limited access to advisory services) as well as the need for improved monitoring and regional differentiation were also mentioned as hindering an effective implementation of agri-environmental measures.

Results- vs. action-based payments

Concerning the innovative approaches, results-based paymentsare an approach where farmers and land managers are paid for delivering environmental outcomes, for example for enhancing the presence of important grassland species. In these schemes, farmers determine the management required to ... More were perceived as potentially (highly) effective in achieving the ecological objectives (especially biodiversity related) due to the agreement of clear and measurable outcomes. Respondents highlighted that rewarding farmers for their environmental performance (instead of compensating for their lost income or increased costs) contributes to the attractiveness of this approach. While the increased flexibility and autonomy for farmers are additional advantages, issues like monitoring (e.g. definition of robust indicators, use of IT or farmers expertise to bring down cost) and risk mitigation (uncertainty due to external factors) still pose a challenge and need some further attention when refining/adapting this approach. Many respondents state that setting up such schemes would require initially large investments (management, monitoring, trainings), which might serve as a barrier for the adoption. As a potential middle ground some experts suggest a combination of results-based payment as a bonus on top of an action-based implementation to rewardRemuneration for current ecological achievements (e.g. biodiversity, climate or water protection) without a necessary additionality. See also: Compensation More more ambitious efforts.

Collective Action

Many respondents agreed that the collective approachrefers to a collection of approaches that involve more than two individuals or parties who are progressing towards a common goal by undertaking collective action. Collective approaches may make use of collective contracts and coll... More (or group contracts) can effectively deliver on the (mostly biodiversity related) objectives when adequate ecological expertise is involved. The main argument in favor of cooperationSee collaboration. More is the positive effect on the connectivity of habitats through a coordinated management of suitable measures on landscape scale. The decreased (real or perceived) transaction cost on the farmers’ side is another advantage. While some respondents argue a long-lived tradition with cooperationSee collaboration. More amongst farmers helps to succeed when collectively implementing measures, others highlight the importance of a feeling of trust within a collective and/or contractual elements for regulating individual behavior being the key factors for success. Regarding the transaction cost of the collective approachrefers to a collection of approaches that involve more than two individuals or parties who are progressing towards a common goal by undertaking collective action. Collective approaches may make use of collective contracts and coll... More respondents acknowledge a shift from public transaction cost (administrations) to the private sector (mainly the collective itself or their management respectively).

Value chain approach

The value chain approach is well received by most respondents, since it seems well suited to rewardRemuneration for current ecological achievements (e.g. biodiversity, climate or water protection) without a necessary additionality. See also: Compensation More farmers for their environmental performance, independently from public funding. The generation of income through an adequate market price is also more in line with farmers’ business logic (instead of relying on public funds). This approach seems to work well with shorter value chains and a more regionalized marketing, while large retailers do often not engage so easily in such programs. A key factor of this approach is the labeling of the extra effort to simplify the decision to purchase for the environmentally conscious customers. Given the already large variety of labels, special attention needs to be paid to a transparent and clear communication of the environmental performance throughout the value chain. Respondents recognize no significant (institutional, cultural or social) barriers to implement this approach, however it is perceived to require an extensive infrastructure and a broad knowledge base.

Land tenureLand tenure is an institution, i.e., rules invented by societies to regulate behaviour. Rules of tenure define how property rights to land are to be allocated within societies. They define how access is granted to rights to use, c... More contracts

The Land tenureLand tenure is an institution, i.e., rules invented by societies to regulate behaviour. Rules of tenure define how property rights to land are to be allocated within societies. They define how access is granted to rights to use, c... More approach is the one with the most uncertainty among the respondents, possibly due to a potential lack of experience with this type of contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More. It could be a well-suited approach for large landowners, especially when intermediaries (National Parks, Church, NGO’s) are involved. The comparatively longer contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More periods of land-tenure approaches not only contributes to the environmental effectivenessis the ability to achieve a desired or pre-defined environmental outcome. More but also benefits the farmer by provided a sound and predictable financial base, where uncertainty and risks are comparatively low.

How does the ideal contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More look like?

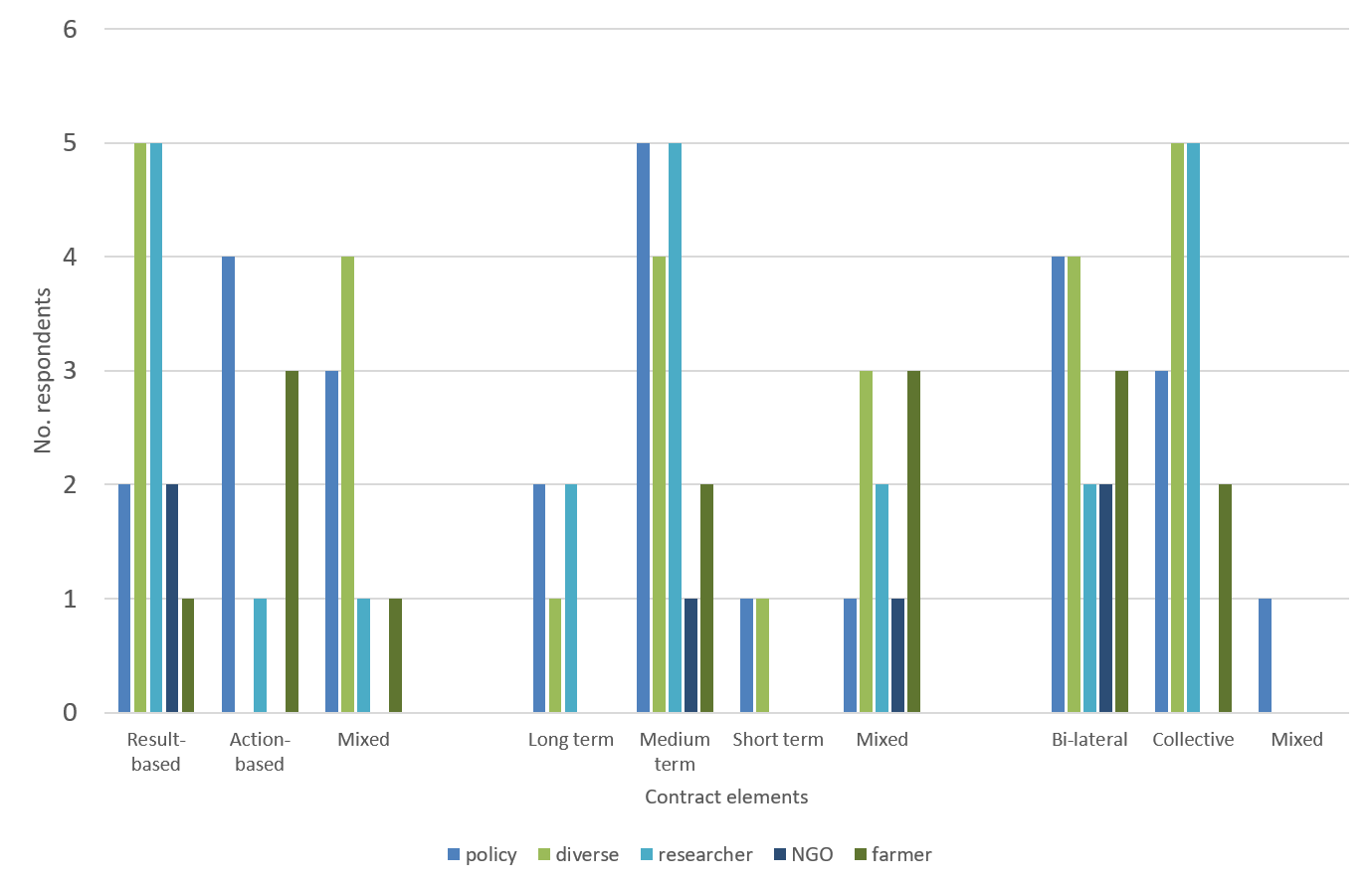

The last block of the survey addressed the question of the ideal contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More. Interestingly the (assumed) most effective type of contracts across all respondents were by far the publicly funded agri-environmental scheme (AES). Regarding the characteristics of a contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More the opinions differ a bit more. Bi-laterally agreed and publicly funded contracts with a flexible length and a mix of results- and action-based payments earned the highest approval rate. Although the results of this survey are far from being representative, the glimpse into the minds of different stakeholder groups involved with the discussion of agricultural policy issues, has provided us with some valuable insights. Especially the open-ended questions have generated a rich pool of ideas, to guide us on our path towards the development of contractual solutions that benefit farmers and nature. The third and last round of the Delphi will be completed in September 2021.

For a more detailed and comprehensive interpretation of the results check out this report.

Figure 2. Differences of the characteristics of the ideal contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More according to the background of the respondents. Source: own compilation based on the 1st round of the Delphi survey.