Farmers’ Perceptions of Payment by Results scheme in UK

Earlier this year, researchers from the UK ‘Contracts2.0’ team spent some time working with Natural England and the Yorkshire Dales National Park’s Pilot Results Based Agri-environment Payment Scheme (RBAPS) to study farmers’ perceptions of this results-based pilot project. Another focus of the joint study was to identify the changes to the management practices as well as the habitat quality of the farmland resulting from the participation in this results-based scheme.

We found that farmers had very positive experiences of the payments by results scheme and, overall, habitat quality was at a comparable level to control sites in conventional agri-environmental agreements. This can be seen as a success considering the relatively short timescale of the project and the additional empowerment of farmers within PBR approaches. Interestingly, many farmers chose to maintain many of their existing management practices, rather than aim to improve the habitat quality as we might expect in a results-based system. Farmers recognised a relationship between their existing habitat quality and the cultural & environmental heritage of the landscape, where unique elements of the area such as ancient flower meadows resulted in sufficient payments. Farmers also noted some important factors outside of their control which impacted management, from the weather conditions to the valuable advice and support received from local project officers.

Our report was submitted to the UK Government’s Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, as a part of the supplementary evidence relating to the ongoing RBAPS trial and development of the new Environmental Land Management Schemes (ELMS) in England.

Project Outline

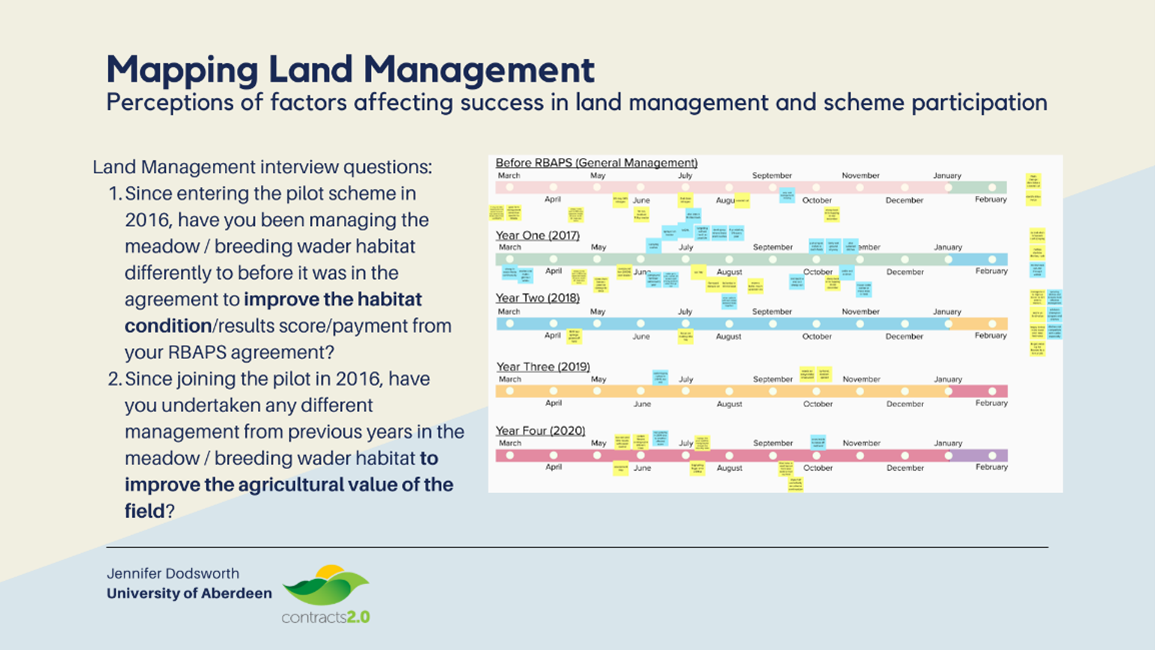

We conducted detailed interviews with farmers involved in the RBAPS pilot in January 2021. The interviews lasted on average for approximately 1 hour 30 minutes, with the shortest interview being just over 1 hour and the longest being 2 hours and 30 minutes. The interviews took place either online via video call (on Skype, Microsoft Teams, Zoom or WhatsApp) or over the telephone. To ‘map’ the farmers’ land management timelines and to compare any changes to management before and during the pilot, we used an interactive online platform called Mural to show farmers the timeline as we were making it. The RBAPS pilot in Wensleydale and Coverdale is focused on Grassland habitats for breeding waders and species rich hay meadows. The upland environments of many of England’s National Parks, and across the UK’s CIL area in the Contracts project, are in many ways ideal landscapes for the delivery of these types of environmental public goodsPublic goods are non-rival (they cannot be exhausted) and non-excludable (there are no boundaries). An environmental example in the Contracts2.0 context is an open and beautiful landscape which can be enjoyed by one person without... More, alongside numerous others.

Figure: Example of a Land Management Timeline made during the interview on Mural

Land Management Approaches in Results-Based Schemes

Motivations and Objectives in Results-based Approaches

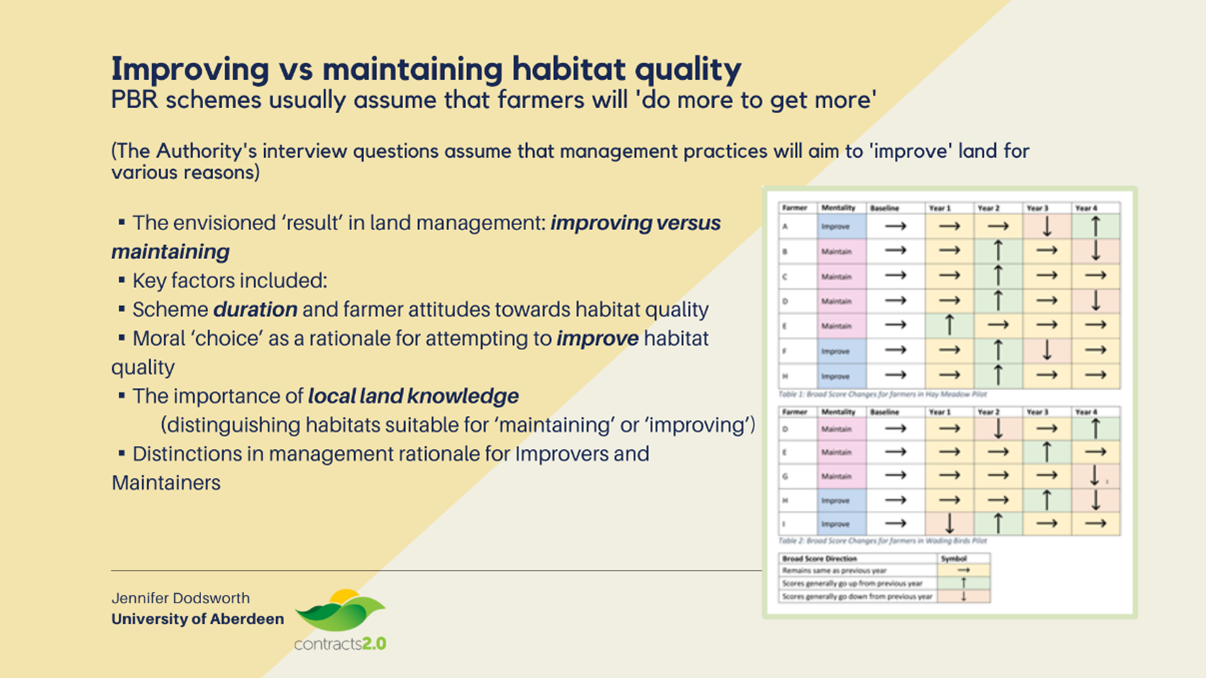

One of the most important factors we identified through our in-depth interviews was a distinction between farmers who aim to ‘improve’ habitat quality and those who aim to ‘maintain’ it through results-based schemes. This distinction between ‘improvers’ and ‘maintainers’ appeared both in terms of motives for habitat quality and the management strategies the farmers employed. The objective of maintaining habitat quality might appear to run counter to the conventional assumption in results-based approaches that farmers will be incentivised to ‘do more to get more’. Though initially surprising, farmers explained that their reasoning for maintaining habitats were many-sided and varied from the short-term scope of the pilot to the existing relatively high standard of their habitats, detailed further below.

Figure: Tracing Farmers’ Land Management Goals in PBR

Environmental Heritage in Protected Areas

Where we found that many farmers were content to maintain the quality of the habitats that they already had, several farmers said that some long-existing cultural environmental features of these habitats, which are unique to protected landscapes, were reasons for their existing good standard. So, where farmers have sought to maintain existing habitats, alongside pragmatic factors of management, they also emphasised the already high-value heritage features of their habitats. These include features more common in National Landscapes, such as

- long-existing uncultivated hay meadows with rare and ancient seeds,

- local & traditional land and animal management practices such as making small hay bales

- locally unique cultural and environmental landscape features such as hay barns

To illustrate, hay barns, for example, are not only highly valued by tourists as beautiful, picturesque features of the Yorkshire Dales National Park, they also hold an important traditional role in practices of small hay bale making, as they enable farmers to house the hay close to the place it was made and where it will be needed for livestock in winter months. Furthermore, this process is one of the most environmentally friendly practices of producing storable forage: the ‘tedding’ (or drying process) redisperses seeds across the meadow. Traditional small bale hay making also avoids issues of soil compaction, where larger bales necessitate heavier machinery, and remove the use of plastic, which is needed to wrap grass for fermentation in silage or haylage production. Therefore, we can see that many of these ‘environmental heritage’ features have both environmentally and culturally valuable qualities which are unique to England’s protected landscapes.

Figure: Hay Barns in Wensleydale (Image © James LePage)

Administration and Support in a Results-Based Pilot

Another factor which was universally identified by farmers as a huge benefit of the results-based approach was the scheme administration. Beyond the highly valued simplicity and flexibility offered by results-based contracts (in contrast to the demanding and complicated paperwork of England’s existing action-based schemes) farmers also emphasised the key role that the National Park Authority (NPA) officers played in scheme support and delivery. Farmers highlighted that the role of the NPA’s local officers in scheme design, information provision, training, and dialogue was fundamental to scheme uptake and success. For the broader developments of results-based schemes, local or regional organisations such as NPAs are, in many ways, well placed to be important intermediary facilitating bodies for these roles.

Issues out of their control: Adverse weather

Farmers also emphasised their habitats’ vulnerability to the impact of the weather, including extreme flooding or conversely, unexpected dry spells. Almost all the farmers made several comments about the negative effect of the weather, particularly when this was combined with differing assessment timings, upon their habitat scores. This vulnerability has important consequences for ‘pure’ results-based schemes, and indicates that ‘hybrid’ schemes, which combine results and action-based, might help to reduce some of the risk to farmers from issues outside of their control.

Disseminating our results

Following our interviews and analysis, we complied a detailed report which was submitted to DEFRA alongside Natural England’s main summary of the Pilot to date. We were also delighted to present some of our recent research into participant farmers’ opinions on payments by results as a part of a national conference ‘Farming with Nature’. This conference, convened by the University of Cumbria, aimed to explore how nature can be delivered within our farmed ‘National Landscapes’, namely England’s main protected areas such as National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs). This approach was a key recommendation from the Landscapes Review.

Future Directions for Wensleydale RBAPS

The pilot is currently running under another extension funded by DEFRA and is exploring alongside the participating farmers how future schemes might work better: Either as ‘hybrid’ schemes which combine elements of action and results-based approaches, or at varying scales which might plan agreements at farm or even landscape levels, rather than individual field parcels.

For more information read our full report regarding Farmers’ Experiences of Results-based contracts in Wensleydale or contact me at Jennifer.dodsworth@abdn.ac.uk or @JennyferDods on Twitter.

Featured Image: © James LePage