“How do agricultural practitioners envision desirable farming landscapes and ideal agri-environmental contracts?” In a detailed report, we collect and present answers to this question. We found that practitioners across Europe envision farming landscapes shaped by viable agricultural practices that strengthen and enhance ecosystem services. It is important that actors in the farming systems share the same values, cooperate and mutually recognise each other’s expertise to make the shared vision a reality. The social setting turned out the most critical change driver, followed by the legal and political framework and land useThe human use of a piece of land for a certain purpose such as irrigated agriculture or recreation. Influenced by, but not synonymous with, land cover (OpenNESS glossary, 2016). See also: Land cover More and environmental conditions. In this post, we share some of our key findings to illustrate what practitioners believe is necessary to unite the socio-economic viability of farming with the production of agri-environmental public goodsGoods where access to the good cannot be restricted and where use by one individual does not reduce availability to others. See also: Environmental Public Goods More in our farming landscapes.

Developing desired landscapes and dream contracts

To answer our initial question, we carried out 28 workshops and consultations in 13 Contract Innovation Labs (CILs) in nine countries across Europe, with a total of 354 participants over the past year. With farmers, environmental NGOs, nature associations, researchers, agricultural advisors and public administrations, we envisioned dream farming landscapes and ideal agri-environmental contracts to facilitate the sustainable transformation of the farming system (see Figure 1). This approach is based on the potential of positive future visions to stimulate sustainable change within the farming system in a participatory way.

Figure 1. Steps from dream contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More development to implementation.

Based on key information provided by stakeholders from each CIL we analysed case-specific situations and problems using swot analysis. We then asked CIL participants to picture a desirable future dream landscape in the year 2040. We encouraged participants to prepare lists of enabling and limiting factors for realising the dream landscape. Finally, we asked them to envision agri-environmental contracts that would facilitate transformation toward the desired state. The participants reflected the contracts from different perspectives such as environmental effectivenessis the ability to achieve a desired or pre-defined environmental outcome. More, socio-economic viability, duration and monitoring. Lastly, we developed dream contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More trajectories – paths to reach the envisioned state.

Common dream landscape patterns

Based on short descriptions the CILs prepared of the dream landscape, we singled out 99 diverse dream landscape elements, which we clustered into eight landscape building blocks: viable and sustainable agriculture, regulating ecosystem services, social cohesion, biodiversity, multifunctionality, enabling landscape managers, health and wellbeing, and cultural ecosystem servicesare defined as "ecosystems' contributions to the non-material benefits that arise from human-ecosystem relationships" (Chan et al., 2012). Further, cultural ecosystem services are understood as "processes and entities that people ... More. We ordered these building blocks into four almost-equally weighted categories: multifunctionality, agriculture-related topics, environmental-related topics and social context.

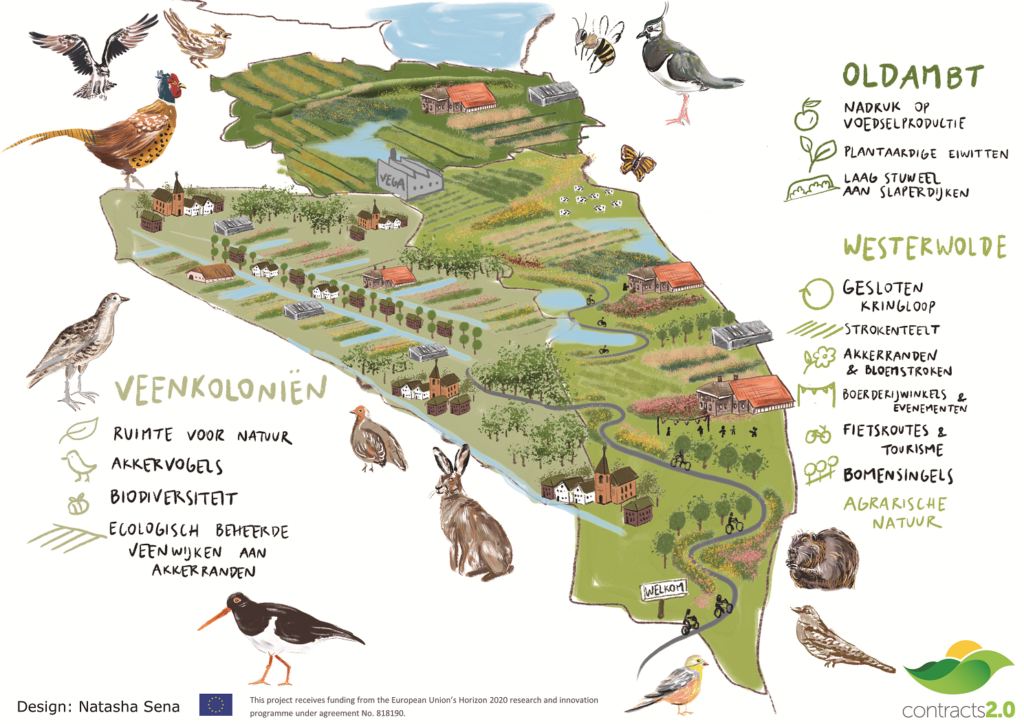

The category multifunctionality is relatively broad and refers to the simultaneous provision of different goodsare the objects from ecosystems that people value through experience, use or consumption, whether that value is expressed in economic, social or personal terms. Note that the use of this term here goes well beyond a narrow definit... More and services of the landscape or through agricultural activities. In the category of agriculture-related topics, the most common landscape element is viable and sustainable agriculture. Viable and sustainable agriculture should be profitable, provide opportunities for new generations of farmers, generate and process quality local produce, apply sustainable farming practices, use and produce renewable energy and optimise livestock production. The category of environmental-related topics includes the landscape elements regulating ecosystem services and biodiversity. Social context consists of the elements social cohesion, health and well-being and cultural ecosystem servicesare defined as "ecosystems' contributions to the non-material benefits that arise from human-ecosystem relationships" (Chan et al., 2012). Further, cultural ecosystem services are understood as "processes and entities that people ... More. Social cohesion is an essential element indicating the importance of cooperationSee collaboration. More, shared values, the connection between communities and the landscape, and vibrant rural living (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Representation of the dream farming landscape in CIL Oost-Gronningen. Several dream landscape patterns are illustrated.

Enabling and limiting drivers of change for the dream landscape

Change drivers are natural or human-induced factors that directly or indirectly trigger a change in an ecosystem. Direct drivers, such as habitat conversion and climate change, are pressures that directly affect ecosystem processed. Drivers that operate at a more diffuse level are indirect change drivers, such as socio-political, economic and technological factors.

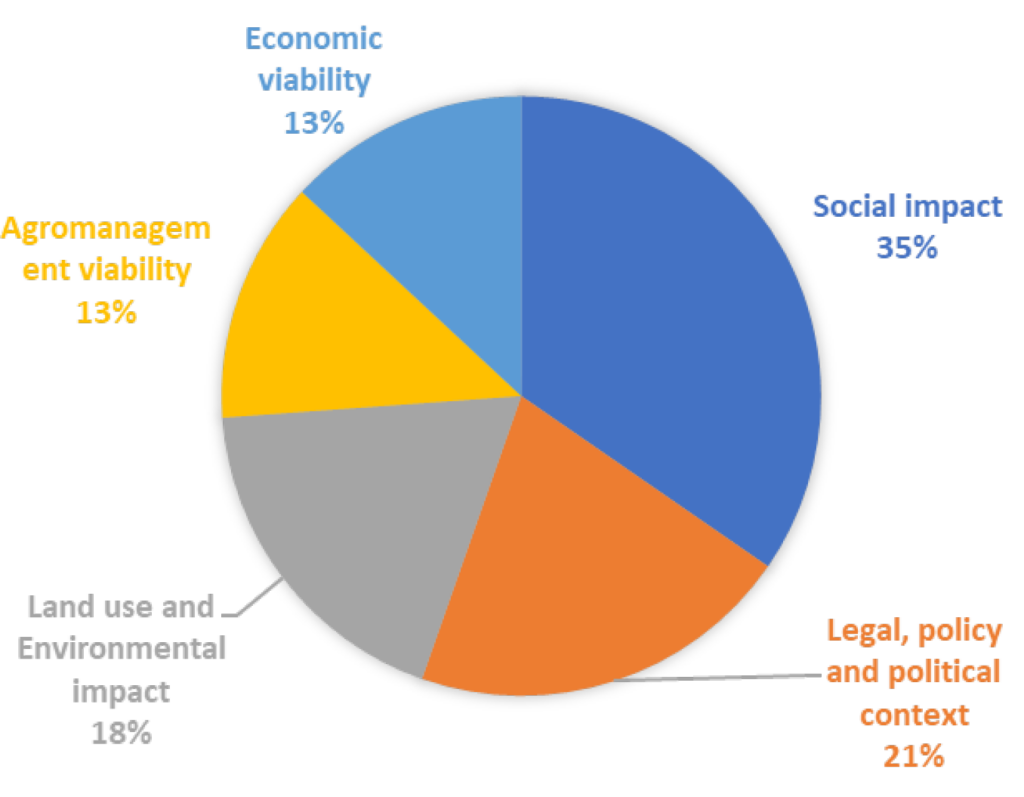

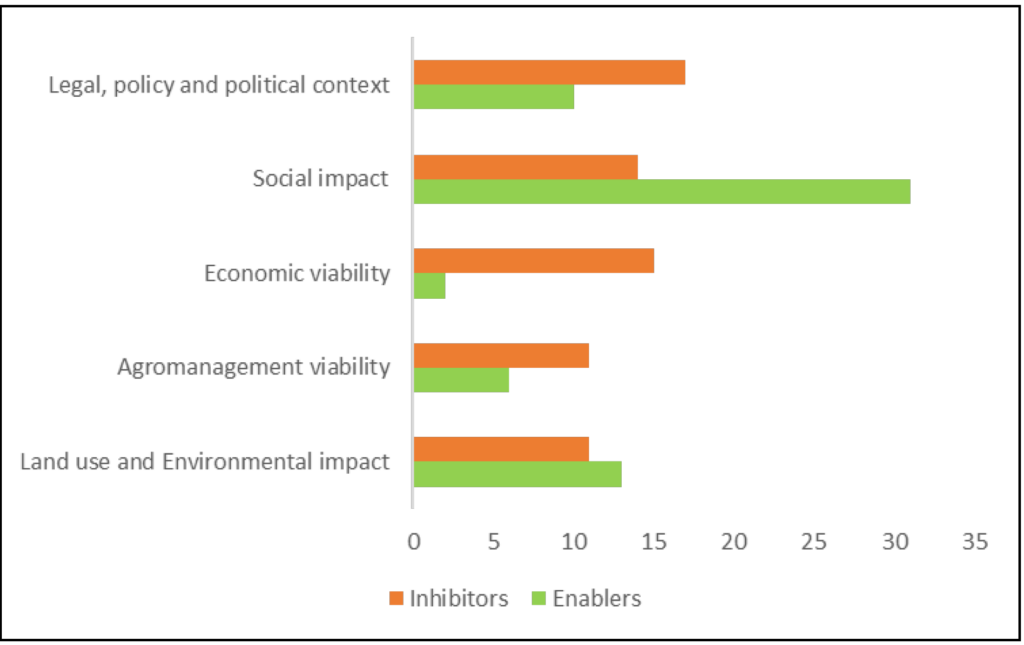

In total, we identified 130 change drivers in our case studies that we assigned to five themes: social impact, legal policy and political context, land useThe human use of a piece of land for a certain purpose such as irrigated agriculture or recreation. Influenced by, but not synonymous with, land cover (OpenNESS glossary, 2016). See also: Land cover More and environmental impact, agro management viability and economic viability (see Figure 3). Across all cases enabling (N=62) and limiting (N=68) drivers are almost balanced. However, each case has a unique profile, which influences the likelihood of achieving the desired dream landscape. The most common them is social impact. It includes enabling drivers such as increased consumer demand, farmers’ intrinsic motivation and cooperationSee collaboration. More amongst farmers. The limiting drivers within this theme were a lack of trust and awareness.

Figure 3. Distribution of change drivers in five themes.

Unlike the three other themes, social impact as well as land useThe human use of a piece of land for a certain purpose such as irrigated agriculture or recreation. Influenced by, but not synonymous with, land cover (OpenNESS glossary, 2016). See also: Land cover More and environmental impact are described mainly by enabling drivers, meaning they are major building blocks for the dream farming landscapes. The limiting drivers are mostly related to economic viability (e.g., market fluctuations), the policy context (e.g., the uncertainty of current and future CAP developments) and agro management viability (e.g., uncertainty on the effects of farming practices) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Limiting and enabling factors across themes.

Dream contracts for dream landscapes

Each CIL developed one or several dream contracts. These dream contracts are legal conduits to strike a balance between farmers’ or land managers’ economic interests and societies’ interests for the provision of environmental public goodsPublic goods are non-rival (they cannot be exhausted) and non-excludable (there are no boundaries). An environmental example in the Contracts2.0 context is an open and beautiful landscape which can be enjoyed by one person without... More and services. We analysed them for general characteristics, benefits, involved actors, payments and monitoring.

General contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More characteristics include the targeted land useThe human use of a piece of land for a certain purpose such as irrigated agriculture or recreation. Influenced by, but not synonymous with, land cover (OpenNESS glossary, 2016). See also: Land cover More and contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More length. Dream contracts targeted diverse land-use types such as grassland (N=12), arable crops (N=10) and permanent crops (N=7). Often, a contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More combines several of these land-use types. The ideal contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More length in most CILs ranges from five to ten years.

The dream contracts envision a wide range of benefits that go well beyond mere financial compensations for farmers (Figure 5). Overall, we identified 96 benefits that mostly help either society or farmers.

Figure 5. Envisioned dream contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More benefits.

We split the financial benefits for farmers into indirect and direct monetary benefits. Direct monetary benefits include income support, cost savings and product added value.

All cases reported the involvement of one or more intermediary organisations. In eleven out of thirteen cases, a farmer group plays a crucial role to broker knowledge, manage payments, coordinate measures, carry out monitoring and build social cohesion.

In eight out of thirteen cases, funding is envisioned to come from the public sector, for example through agri-environment and climate schemes. Two cases aim for private funding and three cases envision a mix of private and public funding. Generally, we observe great interest for collective and results-based approaches, value-chain contracts and combinations thereof. Six out of thirteen cases like to experiment with combining contracts that include action-based and results-based features.

Almost all dream contracts envision that monitoring is carried out in results-based schemes and action-based schemes. We see a strong willingness from practitioners to be involved in monitoring.

Our results in the greater context

We do not claim that our results represent the whole farming community in Europe as they are entirely based on the perceptions of the participants in our 13 CILs, some of whom participated in several workshops. Furthermore, most participants are already engaged in contracts and are interested in reconciling farmer objectives with societal needs for agri-environmental public goodsGoods where access to the good cannot be restricted and where use by one individual does not reduce availability to others. See also: Environmental Public Goods More. Nevertheless, our results give interesting insights into practitioners’ perceptions about desirable changes in present agri-environmental contracts. Practitioners are keen to contribute to societal benefits, experiment with novel contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More designs, and play a more active role in designing and monitoring agri-environmental contracts. These findings can support the design of innovative Agri-environmental contracts and the corresonding policies and Strategic Plans within the New Delivery Model.

To learn more about our findings click HERE.

To learn more about each CIL’s dream landscape and dream contracta formal, written agreement for a specified duration signed by (at least) two parties. In Contracts2.0, we acknowledge the existence of informal contracts but use formal contracts to focus the research. More follow these links:

- Limburg – Netherlands

- Groningen – Netherlands

- Koolstofboeren – Belgium

- Gulpdal – Belgium

- Northwest England – UK

- Hautes Pyrenees – France

- Madrid Region – Spain

- Bornholm – Denmark

- Agora Natura – Germany

- Hipp – Germany

- North Rhine Westphalia – Germany

- Örseg National Park – Hungary

- Unione Comuni Garfagnana – Italy

Written by Sven Defrijn (Boerennatuur Vlaanderen), Marina Garcia Llorente (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid), Edward Ott (Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research), Photo Title: © Illiya Vjestica on Unsplash